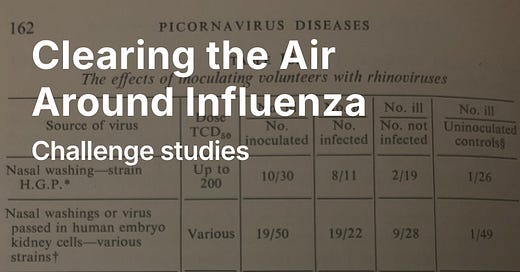

The experiments on human transmission are called challenge studies (or Controlled Human Infection Model—CHIM). Their history dates back at least to Edward Jenner's smallpox experiments over 200 years ago. In the mid-1960s, the director of the Common Cold Unit wrote, “Human volunteers have played a larger part in the study of the common cold than in the …

© 2025 Carl Heneghan

Substack is the home for great culture